The Last Oudmakers of Daramsuq: A Christian Family’s Legacy

DARAMSUQ (SyriacPress) — In the winding alleyways of Old Daramsuq (Damascus), the sounds of a workshop grow faint as an ancient craft fades. Daramsuq is one of the oldest cities in the Middle East, its narrow streets famed for its flourishing craft industry since the Middle Ages. Among the city’s historic crafts — swordsmiths, lace-makers, and silversmiths — one stands out as uniquely Syrian: the making of the oud, a pear-shaped lute central to Arab music.

Syria’s state news agency notes that “the oud is the beacon of authentic tarab” (emotional music) and “an essential part of [Syrians’] intangible cultural heritage inherited from their ancestors.” Even in the 21st century, the instrument’s form is closely linked to Daramsuq. As one expert puts it, a true Damascene oud “is based on grief … sweet sound and warmth.” It is precisely this tradition that Antoun “Tony” Tawil, and now his young daughter Mary, strive to preserve under one workshop roof.

The Oud Tradition in Daramsuq

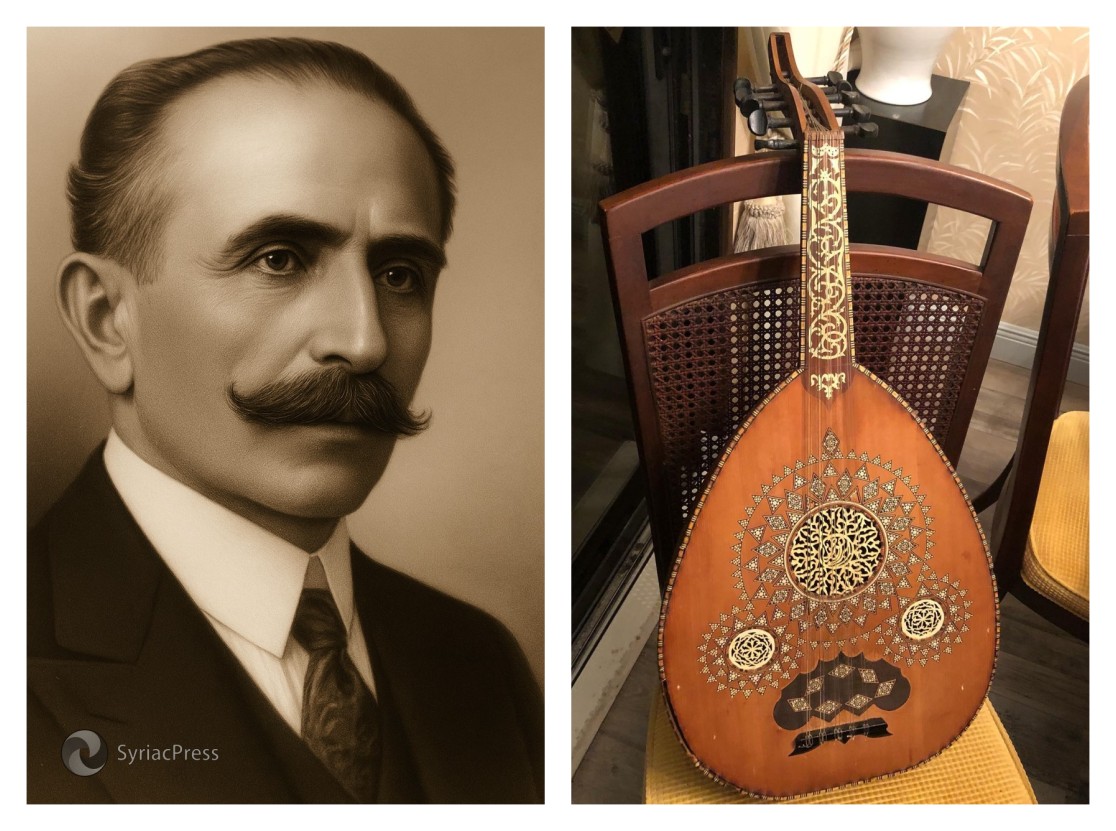

The story of the oud in Daramsuq spans centuries. In 1897, a Damascene craftsman named Abdo al-Nahhat built the first Damascene oud, launching a local tradition. By the early 20th century, the oud was ubiquitous at Syrian weddings and women’s social gatherings. The famous Nahat family — Greek (Rûm) Orthodox from Daramsuq — went on to make instruments often regarded as the finest ever made. In fact, surviving labels and museum examples show dozens of ouds from Daramsuq bearing names like Hanna Nahat, George Nahat, and Toufik Nahat.

One specialist notes that these Nahats were “Christian Arabs.” More broadly, historians record that many of the city’s pre-war musicians and luthiers came from its Christian communities. For example, one 19th-century virtuoso from Daramsuq, Selim Qudmany (also spelled Kutmany), was described as “a Syrian-Orthodox Christian.” Like the Nahat family, these Christians helped make Daramsuq a storied center of lute-making. As a Higher Institute of Music researcher recently observed, Daramsuq still has its own distinctive oud style — one “based on grief … a soulful sound” — handed down through generations of craftsmen and musicians.

Yet, the oud craft in Syria has been under siege. Before the 2010s, Syria boasted roughly 20 oud workshops spread across Daramsuq, Holeb (Aleppo), and Hemto (Hama). But war and emigration have shrunk that number to half a dozen, only four of which are in Daramsuq. Many Old City studios have shut, and even those that remain worry about the future. “It’s a profession under threat,” Tawil says, speaking of the declining market. Young Syrians displaced by war often lack time or training to carry on the craft, and walnut trees, which provide the traditional backing for ouds, are now scarce in nearby Ghouta. Internationally, Damascene ouds still fetch admiration, but domestically, demand has all but vanished.

In the Workshop: Tony’s Story

Tony Tawil, now 64, is one of Syria’s last traditional oudmakers.

In his tiny shop in the alleys of the Bab Touma crafts market, Tawil holds court over dozens of hanging ouds and tools. His previous shop, slightly larger than his current one, was a mere nine-square-meters tucked under the domes of the Tekkiyeh Sulaymaniyeh, an Ottoman-era mosque complex which served as a Sufi convent.

However, the scarcity of space creates a density of beauty. Richly inlaid instruments line the walls. Despite the turmoil outside, he continues the slow, laborious work: selecting and steaming walnut staves, bending each rib by hand, carving the elegant wooden soundboard, and fitting ivory pegs. His hands know every step — he learned them from his father Ibrahim in their Daramsuq home decades ago, and now he carefully shows them to his young daughter, Mary.

Like so many in Daramsuq, Tawil earns little. Before the war, he opened his shop at 7:00 AM and often sold a dozen ouds in a single month. Today, entire months can pass without a sale. The country’s inflationary crisis has seen prices soar but the real value of goods plummet. An instrument that once sold for 5,000 Syrian Pounds (SYP) now goes for 700,000. Despite a price increase of nearly 14,000%, the real value has decreased by 30% — 5,000 SYP used to be roughly 100 US Dollars (USD), it is now closer to .50 USD.

“Before the crisis … so much demand,” he recalls wistfully. “Nowadays, a month goes by without selling anything,” Tony told SyriacPress. Yet in the gloom, he remains passionate about the craft’s splendor. He points to the smooth glow of spruce and walnut, and says quietly, “Our ouds can last 70 years without needing maintenance. I’ve made pieces as beautiful as a Persian rug.” Behind his bench sits an expert from the music institute, Issa Awad, who confirms that it is “the way Damascene wood is dried and cured” that gives these instruments their legendary durability. Tawil often tells visitors that a hundred-year-old Damascene oud still sounds true today — a testament to what he calls “the most exquisite Arab lutes.”

Passing the Torch to a Daughter

Tony Tawil learned the craft of oudmaking from his father Ibrahim, who had himself apprenticed in the 1950s. Ibrahim, a nephew of one of the Nahat luthiers, was also Christian. Like many craftsmen, he learned the trade from his father and is now passing it on to a child. Tony regards his own daughter Mary as the hope of the lineage.

Though still a teenager, Mary already works alongside him every afternoon lining ribs, smoothing sound holes, and memorizing the subtle Eastern tuning. For Tawil, teaching her is a sacred duty. “The oud is still present on many social and cultural occasions,” observers say, and it “has moved from one generation to another.” By involving his daughter now, Tawil ensures that when Syrians next gather for an evening of music or a wedding celebration, a piece of Daramsuq heritage will not be lost.

Even as his workshop empties, Tawil takes heart that the craft has not vanished entirely. “We used to sell to Europe and Canada,” he notes. Indeed, many displaced Syrian artisans carry their skills abroad. He proudly mentions Syrian oud workshops now emerging in Montreal and Paris, saying that “in Quebec, there are now Syrians who are opening their own production workshops.” His daughter’s future may lie in Syria or beyond, says Tawil, but the craft will survive eitherway. Preserving it, he says, is “preserving a large part of [our] memory and the pillars of [our] cultural identity.” For the Tawils, each chiseled walnut stave and each fret slipped on is a note of that legacy.

Throughout Daramsuq’s history, Christians have quietly undergirded the city’s musical arts. The Tawils’ story is one chapter in this tapestry. Syrian (Rûm) Orthodox families like the Nahats and Qudmanys populated Old City guilds, training sons and daughters alike. Rachel Beckles Willson, a scholar of Middle Eastern music, notes that the Daramsuq-born oud virtuoso Selim Qudmany was a Syrian-Orthodox Christian. Likewise, the Nahat dynasty — which forged the first Damascene oud — traced its roots to the city’s smaller communities. In this way, the instrument’s soul and the city’s faith communities have been intertwined.

Today, as Daramsuq reawakens from war, the fate of its cultural heritage hangs in the balance. UNESCO formally recognizes the Old City as a World Heritage site, a living museum of customs and crafts. Within it, the Tawil family works to ensure that one priceless sound does not fade: the mellow, tremolo cry of an oud built by Damascene hands. It is a sound that, in their case, carries both a musical lineage and a family name — one Christian artisan’s legacy played from father to son to daughter.