Assyro-Chaldean Identity: An Invitation

By Fr

The contentious issue of the ethnic identity of the indigenous, Aramaic-speaking people of Mesopotamia can lead not only to debate but community division and erasure, and often becomes the instrument of political propaganda and emotional outrage more than calm discussion. Nuance is left behind in favor of oversimplified pandering to one opinion or another, and just as is often the case in politically-adjacent questions, the most extreme positions can become the most popular. On social media, the worst elements are encouraged, often with Chaldeans and Assyrians claiming exclusive naming rights or separatism from one another, and most recently, Kurdish ethno-nationalist extremists arguing that any Chaldean or Assyrian claim on Mesopotamian cultural heritage is a modern fabrication. Things get even more complicated when the question is expanded to communities with historical roots outside of Mesopotamia proper, and Suryoyo divide between presenting themselves as Arameans or as Assyrians. On the other hand, because history is never as black-and-white as pundits pretend, scholarship can offer a relatively detached analysis, but can often lack the energy to dive into the question with the interest required for a deeper understanding. So in the midst of all this, I thought I’d add my two cents. What follows is offered in a spirit of honesty and peace, but you can of course take it or leave it as you see fit. If the last few decades have taught us anything, it’s that we will never force ourselves to unity.

Let me start this by saying, first, that I am speaking for myself not as a priest or representative of the Church but only as an individual, as everyone has a right to do. Second, I’ll state again for the record that I’m not a “Chaldean separatist,” and believe Chaldeans and Assyrians are fundamentally one people. This alone will get me in trouble with one side of this debate which has some prominent adherents, but that’s life. The fact is, our forefathers lived and breathed and prayed together, and they were persecuted and martyred together, as our people still are today.

I do not, however, agree with the common talking point “Chaldeans are Catholic Assyrians.” Chaldean is and has always been an ethnic name, and if it’s also the name of a Church, that’s because the Church is named after an ethnicity, like the Armenian Church, the Russian Church, and the Assyrian Church of the East. Granted, our people quite often identified themselves along religious grounds (“Christian,” “Nestorian,” “Catholic,” etc.) rather than according to ethnicity, and that’s one of the big reasons there are relatively few historical sources that discuss our ethnic identity at all.

So we are left in the admittedly confusing position of being one people with two ethnic names. It’s confusing, but it’s not new. One example of this I’ve already discussed is that centuries ago, well before any split in the Church of the East or attempted Catholic union, Michael the Great, relying on even older authors like Josephus, used both terms, Assyrian and Chaldean, to refer to the ethnicity of Aramaic speakers East of the Euphrates, with “Chaldean” considered, at his time, the most general and ancient ethnic name for them all. The fact that it’s now (mostly) Catholics who currently call themselves “Chaldean” and (less-mostly) non-Catholics who call themselves “Assyrian” is the main internal problem our people face today – and it is a problem that did not exist until the bloody middle eastern politics during and after World War I. It did not at all have to be this way, and in fact was not this way until quite recently. Both names were used at various points in history to name our ethnicity, and quite often together. Rather than be ashamed or confused by this, or attempt to suppress one of the names or separate as a people, we lose nothing by all of us embracing both ethnic names as expressive of the Mesopotamian cultural identity we have all inherited.

I should state here that I’m talking about the actual historical usage of the names “Chaldean” and “Assyrian.” The cultural or genetic connection between our people today and the ancient Chaldean and Assyrian empires is a very interesting, but somewhat different, question from that of terminology. For the record, I think there is such a connection, and it’s just as complicated as the issue of names.

Interchangeable Ethnic Names

The historical record is quite clear that Chaldean does not mean “Assyrian Catholic.” For one thing, non-Catholic (“Nestorian”) Patriarchs of the Church of the East (re-named the “Assyrian Church of the East” in 1976) have at times claimed to be ethnically Chaldean, a fact that persisted until as late as 1911. Assyrian scholar John Joseph (who, though not infallible, has still written the most comprehensive study on this issue to date) notes this:

“The usage and origin of the name Chaldean has also been the subject of much acrimonious debate. While this term is generally accepted today as referring to the Roman Catholic off-shoot of the Nestorian Church, it has in the past been used as a national name in reference to both branches. Nineteenth-century European writers, in order to distinguish between the two churches, have referred to them as Nestorian Chaldeans and Catholic Chaldeans.” (John Joseph, The Modern Assyrians, 3-4)

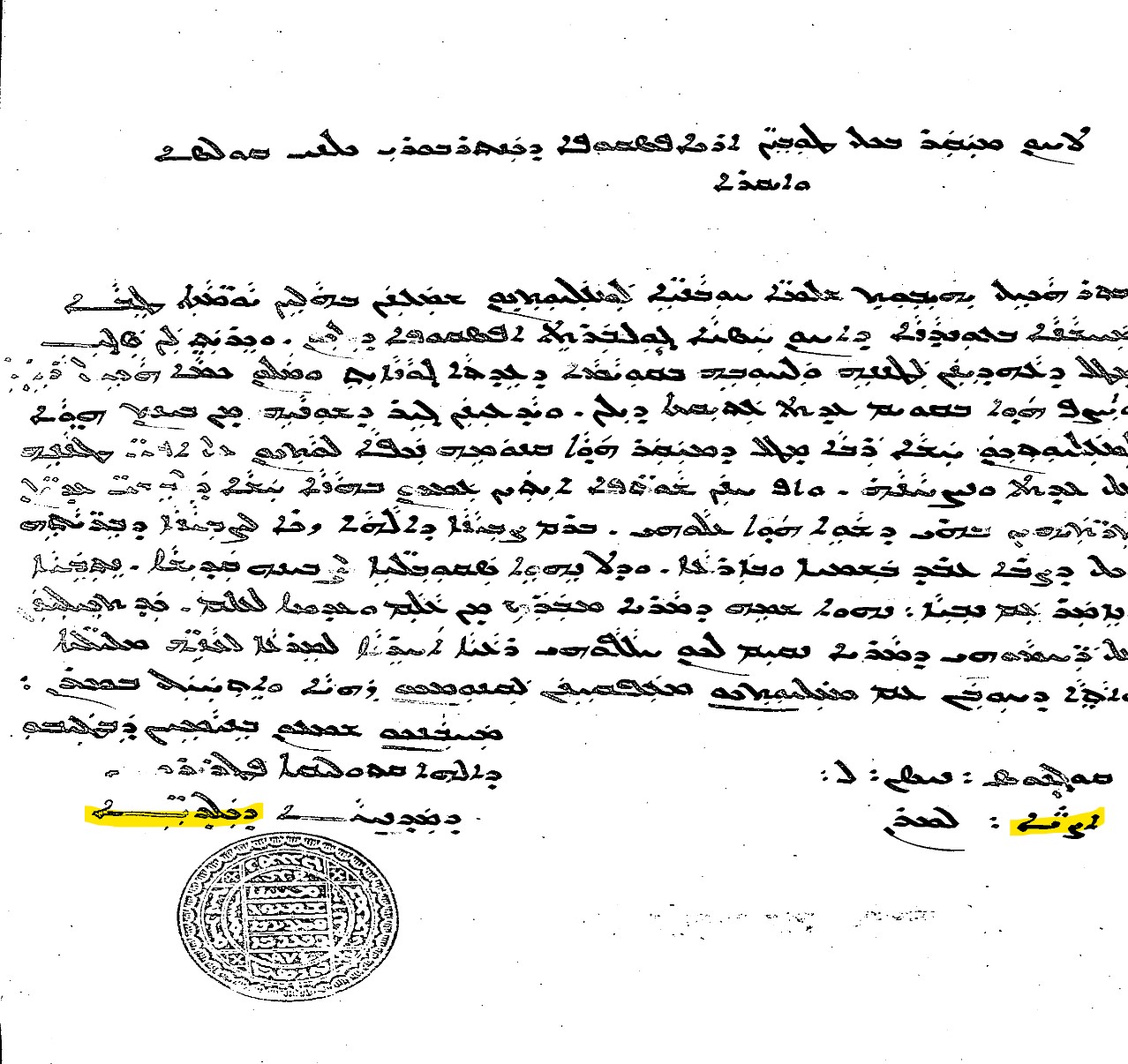

The same scholar quotes Horatio Southgate, who in the 1830s wrote that the Nestorians “’call themselves, as they seem always to have done: Chaldeans;’ indeed, ‘Chaldean’ was their ‘national name,’ he stressed.” (p. 5). With this in mind, it shouldn’t come as a big surprise that the “Nestorian” Patriarch referred to himself as “Patriarch of the East of the Chaldeans” as late as 1911:

Granted, the martyred Mar Shim’un Binyamin traced his Patriarchal line (which continues now in the Assyrian Church of the East) back to Mar Yohannan Sulaqa (who famously or infamously began our first attempt at union with Rome), and this is shown in the seal underneath the signature above. But my point here is that the word “Chaldeans” did not mean “Assyrian Catholics.” Above we see the leader of the non-Catholic branch of the Church of the East naming his people “Chaldeans.” How exactly the branch that was originally Catholic later became the Assyrian Church of the East, and the non-Catholic branch later became the Chaldean Catholic Church, is a complicated and amazing story (summarized as well as possible in chapter 8 of The Martyred Church).

On the other hand, the fact that Catholic Chaldeans also understood their name to be an ethnicity, not merely a religious or denominational name, is clear well before 1887, when Patriarch Putrus Eliya XII used the terms umthan dylan kaldayta, “our Chaldean nation,” in his introduction to the Hudhra (see my Book of Before & After, xlii), similar to the term sharibtha d-kaldaye “the tribe of the Chaldeans” used as a community self-designator by Patriarch John VIII Hormizd before 1830. This is not at all a new usage, and is consistent not only with the inherited assumptions of Michael the Great going back to Josephus and earlier, but also with the usage of the term “Chaldean” by the Church of the East, for example by Patriarch Hnanisho’ II, whose Synod of 775 describes the importance of the Diocese of Kashkar in these words:

“For Urek is Abraham’s city, the father of the nations, as it is written, ‘I am the Lord your God who brought you out of Ur of the Chaldeans to give you this land to inherit.’ Again, Kashkar is the same as Ellasar, which is from ages and generations ago, a kingdom which ruled the land of Shinar, according to the testimony of the son of Amram.” (Birnie, p. 182)

I repeat, I’m not talking about the historical questions of whether there was an Abraham, whether he was from Ur, or whether Ur was of the Chaldeans. I’m talking about the use of the term Chaldean, and whether it was used as an ethnic name before any Catholic union, which it was. In fact, it was only a few decades after this that Patriarch Timothy I made Abraham of Ur a representative of his entire Church, not just one diocese. There are many other sources and authors that use “Chaldean” as an ethnic term (though not always as their own ethnic identifier), like Isho’dad of Merv and Thabit Ibn Qurra in the 9th Century, Elia Bar Shinaya in the 10th Century, Michael the Great and the Cause of Causes in the 12th Century, Bar Hebraeus in the 13th Century, etc. It’s worth noting, however, that it was very rare to find the term “Chaldean” referring to a distinct people from the rest of those in Mesopotamia. It was either used in conjunction with “Assyrian,” a synonym for it, or a collective term encompassing all Assyria and Babylonia, that is, north and south Mesopotamia. I will say more about this below.

In any case, the idea that Chaldean ethnicity was invented by the Catholic Church in the 1500s or first promoted only in 1980s Detroit or before the 2000 American Census, and that beforehand everyone understood themselves to be ethnically Assyrians, is a complete fantasy (though admittedly, Chaldeans have often been apathetic to the question of their identity). On the other hand, leaders of the Chaldean Church have at times self-identified as ethnically Assyrian or appreciated their Assyrian heritage, from Bishop Toma Audo to Patriarch Raphael Bidawid. Chaldean ethnic separatism is equally a fantasy. I don’t think there’s a need to make an extended argument about the legitimacy of the Assyrian name. In general, especially in the last several decades, Assyrians have done their homework on their identity, and Chaldeans could learn from their example.

The fact is that, historically, all of our people have properly been named both Chaldean and Assyrian, and both names have been understood to be expressing ethnicity. This fact will be as annoying to Chaldean separatists as it will be to Assyrian extremists, but the talking points of both are simply wrong. Chaldean is an ethnic name, but (at least in the Christian era) it did not refer to a separate people from Assyrians. They were both understood to be completely valid, interchangeable ethnic terms to refer to one and the same people. And if both of them are valid, it seems obvious that neither one should be erased as an ethnic term today. At the very least, it’s not nearly as black and white as some people pretend, and the name one chooses to use is a judgment call that each person deserves to make for themselves.

Here’s the option I personally think is best both historically and practically:

The Assyro-Chaldean Tradition of Combining Names

If it bothers you that our one people have two ethnic names, then I invite you to combine the names into one, as intelligent people have been doing explicitly for over a century. This idea hasn’t often been successful historically (I think mostly because our people are famously stubborn), but I’m naive enough to hope it can be revived in the younger generations.

Here is a selected handful of examples showing how the combined name naturally developed (I’m sorry that many of my references are from clergy; even though this is not a religious issue, for much of our history, it was mostly clergy who knew how to read and write):

- In the 8th Century, Patriarch Timothy I claimed all of Mesopotamia collectively as his own heritage, from Abraham of Ur of the Chaldeans to Nimrod who built Babylon and Nineveh.

- In the 12th Century, Michael the Great combined the terms Assyrian and Chaldean in describing the Aramaic-speaking people East of the Euphrates river.

- In 1860, Fr. Joseph Gabriel discussed the Chaldean nation (umtha) and says other cultures received their sciences “first from the Chaldeans, or Assyrians, which means the same thing.” (Becker, Revival and Awakening, 316).

- In 1897, Hurmizd Rassam, in Asshur and the Land of Nimrod, says that all the Christians of Mesopotamia have “the same Chaldean or Assyrian origin.” (Becker, Revival and Awakening, 305).

- In 1912-1913, Bishop Addai Scher combines the names Chaldean and Assyrian in his two-volume history book Kaldu-Ashur.

- In 1919, all our people presented themselves as “Assyro-Chaldeans” at the Paris Peace Conference.

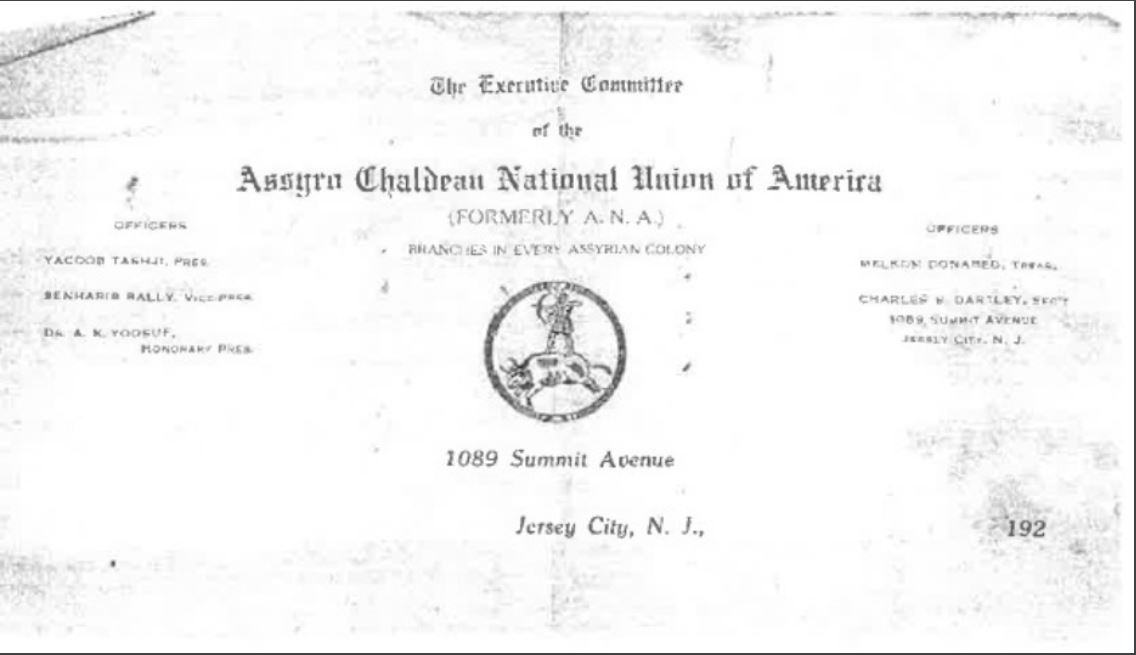

- In 1920, the “Assyrian National Association of America” changed its name to the “Assyro-Chaldean Union of America.”

- In 1923, Rev. S. David publishes, The Assyro-Chaldean History, Edited and Printed in the Neo-Chaldean Language.

- Military leader Agha Putrus (1880-1932) promoted and popularized the term “Assyro-Chaldean” (see Frederick Aprim, here, as well as Yasmeen Hannosh, “Minority Identities Before and After Iraq: The Making of the Modern Assyrian and Chaldean Appellations,” in The Arab Studies Journal 24.2 (2016), 29).

Only if we understand all of Mesopotamian heritage collectively can we lay claim to its totality. It is not enough to say (citing Michael the Great), that “Chaldean” was for centuries used as the collective name for all Aramaic-speaking Mesopotamians, when today there are many of our people who identify, correctly, as Assyrians. Nor is it enough to declare that today, the collective term for all indigenous Mesopotamians should be “Assyrian,” when there are many of our people who identify, correctly, as Chaldeans. These are terms naming one and the same people. Leaders of both the Catholic and the so-called “Nestorian” branches claimed the Chaldean name and ethnicity as recently as 1911, and both branches also inherited the liturgies of the Ba’utha of the Ninevites, apparently expressing a connection to Assyrian heritage. Making the issue black and white, and demanding that people choose only one name and reject the other, or pretending that only one ethnic name was used, or claiming that Assyrians and Chaldeans are two different people today, goes against the facts of history.

This isn’t a game, but maybe an analogy can help explain what I’m getting at. Online, you’ll see Chaldeans and Assyrians arguing with each other and making lists of quotations from historical sources validating the Assyrian or Chaldean name (in some cases, all an ancient author has to do is use the word Assyrian or Chaldean to be counted as someone who identifies as such). The implication is that whoever has the longer list has the most points, and wins, and the other side has to change their name because my side won. This game is ridiculous and becomes an exercise in dishonesty and cherry-picking almost every time it’s played, and forgets that the few documents we have that survived the fires of history might not tell the whole story. Definitely not enough to force someone to change their name, as if we could ever do that in the first place.

But let’s play the points game anyway. If one day, Team Assyrian finds 26 documents that validate the Assyrian name, and Team Chaldean finds only 14 documents that validate the Chaldean name, the score is 26 to 14, with Team Assyrian winning. It’s often said that “Chaldeanness” at some point carried the meaning of something like “magic,” and therefore gave a negative connotation in Christian contexts; this is indeed the definition we find, for example, in the Lexicon of Bar Hebraeus. Keep paging through the same Lexicon, however, and look at the definition he gives for “Assyrian,” which is “enemy.” That’s minus 1 point for both Team Assyrian and Team Chaldean. But those aren’t the only two teams. If Assyrian gets 25 points and Chaldean gets 13 points, Assyro-Chaldean gets 38, because it is not a denial of either but an embracing of both.

Imagine the collective breath we could all take if we could accept this kind of unified identity and stop fighting among ourselves. But as it is now, we care more about winning than about the truth, and because of that we can’t accept the truth as it is, since it’s more complicated than either “side” wants it to be. So what we’re left with is oversimplification, dismissal, name-calling, and ultimately separation. One side demands that everyone take its name as a prerequisite for unity; the other side would prefer to keep its name and would rather separate than lose it. Both sides are prideful, neither is on the side of history, and we all end up losing.

Patriarch Timothy I understood his people to be the heirs of both Abraham of Ur of the Chaldeans, as well as Nimrod the gabbara who built Ashur. It’s worth noting that even at his time in the 8th Century, there was already no value in distinguishing the ethnicities of north and south Mesopotamia, which some extremists are so fond of doing nowadays. For Timothy already, as well as for Michael the Great a few centuries later, the Aramaic-speaking people of Mesopotamia were a co-mingled, united group. Even the 5th-Century Doctrine of Addai mentions that Abgar wrote to Nerseh, “King of Assyria,” who was “ruling from Babylon,” and the Bible talks about king Nimrud who built both Nineveh and Babylon. The sharp, divisive stress on the distinction between north and south Mesopotamia seems to be more of a modern idiosyncrasy, while understanding Mesopotamia collectively seems to have been the standard through most of history. How much more must this be the case so many centuries of war, captivity, and migration later?

Here’s an example from my own family history. I was born in Detroit; my father in Baghdad; his father in Alqosh; his father (from what we can tell) in Mengeshe; his father (a “Nestorian” priest) in Gaznakh. Before that (some time in the early or mid-1800s) we don’t even know a name, much less where anyone lived. Every single generation in living memory moved villages without exception, and there are over 2,400 years between the earliest family member we can trace and the end of the Assyrian empire. I find it unlikely that for 2,400 years nobody moved, and then exactly 5 generations ago my family decided to move every single generation. Yes, the last couple centuries have been pretty chaotic, but the Middle East wasn’t exactly peaceful beforehand. In other words, I think being too precise with our geography might not be supported by reality. Incidentally, on my mom’s side, we have her and her siblings born in Baghdad, her dad (my grandfather) born in Baghdad, and his dad also born in Baghdad. We’re not quite certain whether his dad also was born in Baghdad or in Tilkepe. Not sure why I’m sharing that, but I think it’s interesting.

In any case, if I haven’t already made this clear, the supposed distinctions between modern Chaldeans and Assyrians (whether religious or geographical) do not at all map onto the distinctions between ancient Chaldeans and Assyrians. At least I’ve found zero decent evidence of this. There are certainly regional variations today in food, dance, or language (put someone from Tilkepe and someone from Urmia together, and they might end up speaking English), but these variations are much more related to villages than to any supposedly separate Chaldean or Assyrian ethnic identity. Even my own grammar books use the term “Chaldean Language” to mean “the dialect of Aramaic that is spoken by people who mostly identify as Chaldeans today.” It’s not the language (or, to be precise, the dialect) of the ancient Chaldeans, just as the term “Assyrian language” used today is not the language/dialect of the ancient Assyrians (though all of them are of course related). It’s an accident of history that the names fell as they did, but it’s a fact we have to deal with. Oh, and if you’re trying to learn the language, which you should, there is a full series of videos to help you do that, as well as children’s books. While we’re talking about language, one of my big pet peeves is when our people disparage each other’s dialects. We should absolutely clean out Arabic and Persian loan-words as much as possible, and I’ve worked as hard as anybody to make that happen, but there are legitimate differences in our dialects that should be seen as varieties, not as competitors.

Once in a while, out of frustration with the complexity of all this, people will offer the solution of adopting a whole new name, like “Mesopotamian” or “Babylonian” (the first word being Greek and the second word used more rarely over the last two millennia than either Assyrian or Chaldean), or just transliterating the word “Suraya” into English (more on this word below). I don’t see any reason for this. We have two perfectly good names already, and there’s no need to add more. Another big issue, which we gloss over all the time, is that it’s a really big deal to ask someone to completely change their name, and we’d better have a good reason to do it.

Asking someone to change their name is one thing, especially when this request is based on an agenda-driven cherry-picking of history. Asking them to expand their name is another thing entirely, and is very much part of the tradition we have inherited. Unity by force, absorption, or erasure will always and only lead to further separation and separatism, because force is repugnant. Unity by expansion and openness, acknowledgement of the true complexities of history, and friendly family dialogue, is the only real unity. Our national pioneers of the 19th and 20th Centuries, including the great general Agha Putrus, understood this when they used terms like “AssyroChaldean.” We who have never fought in a war outside of the internet do not yet have the same courage.

This combined name is one with a pedigree of over a century, and deserves respect. What would the reasons to reject it be? Inconvenience? Assyrians are often asking Chaldeans to completely change their name for the sake of unity. Are Assyrians willing to expand their name for the same cause? Which is a greater inconvenience? A total change or an addition? What other reasons would there be? Racism? My fellow Chaldeans, the Assyrians are your own people. I know your grandparents want you to marry from the same village, but you’ve never seen that village and couldn’t find it on a map if you had an hour to look. What other reasons are there to reject a combined name? Aesthetics? The hyphen doesn’t look nice in your social media bio? How low of a priority is unity if that’s how little you’re willing to sacrifice? What other reasons would there be? That the name shouldn’t be such a big issue, and Chaldeans should just call themselves Assyrians, or that Assyrians should call themselves Chaldeans? If the name isn’t a big issue, then both Assyrians and Chaldeans should be fine with Assyro-Chaldean.

Names are, for the record, a very big issue, and all the fights over our name have proven that. Unity is a bigger issue, but “unity on your terms or no unity at all” is a very bad place to start. Name-calling, “cancelling,” or (most common of all) bashing the reputation of anyone who doesn’t accept your entire narrative is not dialogue, and will never lead to unity. Humility on every side, adherence to the fulness of history, and mutual sacrifice might. Isn’t it a weird coincidence that every single writer who questions some narratives suddenly turns out to be a terrible person? It’s almost like the propagandists want to send a message to anyone else who might think of questioning them. They censor anyone who disagrees with them and call the result a consensus. This is the exact opposite of dialogue. I’ll save everyone some trouble: I’m definitely a terrible person. But that doesn’t mean anything I’m saying here is wrong.

The Name Suraya

If you feel like making things even more complicated, look into the history of the word Suryaya or Suraya, which most Chaldeans and Assyrians are used to hearing as an Aramaic word identifying us, and relatedly, the word Surath identifying the dialect of Aramaic we speak. On the surface, the name Suraya sounds like it means “Syrian,” which it does in some cases. But there’s a good argument to be made (and Assyrian researchers have done an admirable job of tracing this) that the historical root of the word is “Assyrian.” This shows up more clearly in English than it does in Aramaic: “Syrian” and “Assyrian” look very similar. In Aramaic, Suryaya and Athuraya do not, but there are linguistic reasons that Ashuraya could have turned into Assuraya and then into Athuraya.

Great. But the problem is that etymology is not the same as definition or intention. Even if Suraya historically traces back to the word for Assyrian, that doesn’t mean that everyone who says Suraya means “Assyrian” when he says it. Roots of words are not the same as their meanings. Here are some examples: the root of the word “Andrew” is the Greek word for “manly,” but that doesn’t mean that when people call me by my name, they are saying I’m manly. The root is lost, and the word takes on a new meaning to the people speaking it. When you call someone “human,” you’re using a word whose root is the Latin “humus,” which means “dirt.” Do you mean “dirt” when you call someone “human?” No (or hopefully not); the root is not the same as the meaning. The examples of this are practically infinite. Etymology is not the same as meaning.

Among some Iraqi Chaldeans today, the word Suraya can have the meaning of “Christian.” Ask your grandmother whether the Pope is a Suraya. If she says “yes,” it’s unlikely that she thinks the word means “Assyrian” (even though the Pope is from Chicago). This definition of Suraya isn’t new either. In 1852, a “Nestorian” patriarch was quoted by George Percy Badger using the term in exactly this way: “We call all Christians Meshihaye, Christiane, Sooraye, and Nsara; but we only are Nestoraye.” (G. P. Badger, The Nestorians and their Rituals, vol. 1, 224).

The second problem is a historical one. We’re all used to hearing our aunts and uncles call themselves Suraye, and whatever they might mean by it, I don’t think it’s even close to true to say that our people “always” called themselves by this name. I actually think it’s much more recent than you might guess (like the organization of Church traditions into “East Syriac” and “West Syriac”), and I have yet to see much evidence to the contrary. At least during the middle ages, it seems clear that Suryaya was mostly used as a synonym for Aramean (the “sons of Aram”), and specifically (at least in Michael the Great’s assumption) referred to the Aramaic-speaking people west of the Euphrates, with “Assyrian” and “Chaldean” (according to Michael, the “sons of Ashur and Arpachshad”) being names reserved for people east of it. Indeed, in Michael’s inherited usage, Suryaya and “Assyrian” are assumed to be opposites (or at least non-overlapping), until he makes an argument based on an adjusted meaning of Suryaya.

An expanded usage, implied by Michael’s argument which I explain in my post, might be that Suryaya could also mean any Aramaic-speaking people, regardless of ethnicity, and it’s this meaning that Michael uses to claim that Assyrian and Chaldean kings can be counted as Suryaye because of their “Aramaic tongue and education.” But this is an argument from language, not from ethnicity, and Michael the Great knows it, since he still acknowledges the different ethnic origins of the people east and the people west of the Euphrates. Even though the ancient Chaldeans (and eventually also the ancient Assyrians) spoke Aramaic, they were not the only people or ethnicity to do so. I think this linguistic sense is the one in which Mar Abdisho’ of Nisibis used when cataloguing “Syriac authors.” In other words, he was listing authors who wrote in Syriac, the dialect of Aramaic, and was interested in their written language, not their ethnicity. The same goes (pretty obviously) for the many grammar books of the Lishana Suryaya written by our forefathers, explaining the Aramaic dialect specifically of Edessa (in Syria). With this history in mind, I think it’s likely that the origin of our people’s use of the term Suraya as an identifier is a linguistic one, not an ethnic one. Suraye are people who speak Surath, or (more technically in modern terms) Neo-Aramaic, and so this name applies to us in the linguistic sense argued for by Michael the Great. Incidentally, at some point one common term in the Latin-speaking world for “any Aramaic-speaking person” was “Chaldean.” Michael the Great seems to be aware of this kind of usage as well, though when he uses the term he seems to limit it to people within Mesopotamia. The definitions of words are never as black-and-white as we want them to be.

I could be wrong, of course. Exactly when and why Assyro-Chaldeans began calling themselves Suraye as a community grouping-term seems like an under-studied question, and one I’d love to see more evidence about. But certainly by the middle ages, the word Suryaya meant at most “any Aramaic speaking person,” and did not usually refer to Assyria in any direct way. Indeed, if the eventually-accepted definition of Suraya at some point became “Aramaic speaking person,” and if most Christians in Mesopotamia and Syria were Aramaic-speaking, this helps explain how Suraya can sometimes even mean “Christian.”

In any case, if today there are Suryoyo who identify as Assyrians, that’s great, and the term Assyro-Chaldean will therefore include them. If there are some who do not, and if a political party or organization wants to respect and represent all of them, then Chaldean-Assyrian-Syriac included in the name of the party or organization might be one somewhat-cumbersome option (and for the record, I neither support nor am supported by any Iraqi or American political party, and I don’t think anyone should support, or not support, a party just because they use a particular name). If you don’t like this multiplication of names, I’d remind you that mutual respect is sometimes inconvenient, and actual unity based on history is more important than aesthetics. Personally, I think Assyro-Chaldean sounds great (nobody has a problem with Anglo-Saxon, Greco-Roman, Indo-European, Franco-Norman, Judeo-Christian, etc.), and I’d be much happier if everyone called themselves that, even more than if everyone called themselves only Chaldean or Assyrian.

One quick final note. I’ve used the term Assyro-Chaldean because the names there are in alphabetical order and the term has been used before, but Chaldo-Assyrian is great too, and I don’t want to give the impression that I’m imposing my preference on anyone. I also don’t really think the hyphen is necessary, and AssyroChaldean / ChaldoAssyrian, or even Assyrochaldean / Chaldoassyrian could be fine if people prefer it. People get a voice in determining their name, which is why this is a matter of education and persuasion more than force or pressure. In fact, it’s reasonable to take baby steps even toward a unified name, and begin with terms like Assyrian-Chaldean or Assyrian/Chaldean, and move forward from there. But every step has to be taken freely by all of us who are willing to walk together.

This article was originally published on younan.blog on 27 July 2025. The original can be found here.

The views expressed in this op-ed are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of SyriacPress.