Kessab: Syria’s Enduring Armenian Enclave on the Edge of Conflict

KESSAB, Syria (SyriacPress) — Kessab’s cluster of white-stone houses, with the red-tile dome of its Armenian church glowing at dawn, lies like a patch of Armenian homeland on Syria’s Mediterranean coast. For nearly a millennium, ethnic Armenians have lived here — ancestors of Syria’s ethnic Armenians, Christians who have lived here for a millennium. Yet Kessab’s story has been one of repeated upheaval.

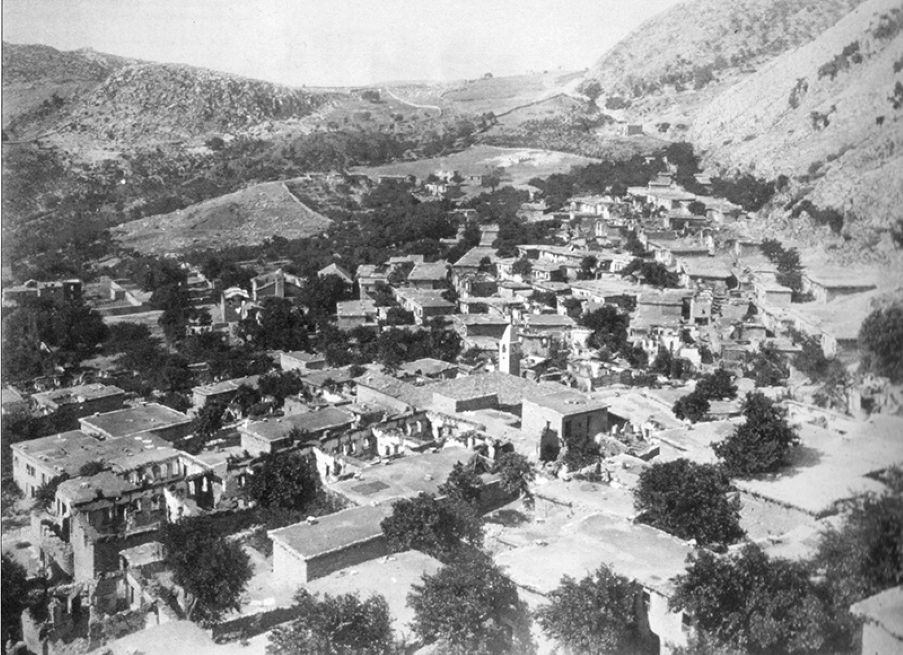

In 1909, Turkish gunmen razed part of the village, but locals quickly returned and rebuilt, opening an orphanage and women’s union to aid the survivors. In 1915, the Ottoman Empire again deported Kessab’s Armenians — roughly 5,000 were sent on deadly marches, a part of a much larger genocide of the Empire’s Christian peoples. By 1918, most survivors had come back to rebuild once again. In the 1920s, Kessab’s Armenian population swelled to about 3,500. Over the decades many emigrated abroad, but before Syria’s civil war in 2011 about 1,500 Armenian-Syrians still called Kessab home, maintaining their church, school, and cultural center against all odds.

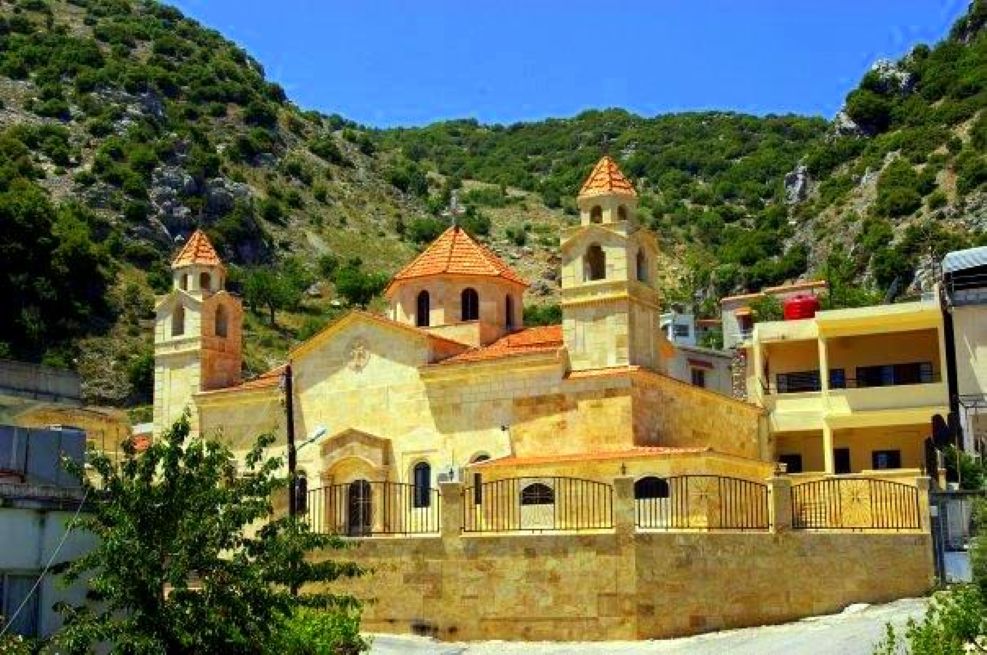

Church bells still mark the week in Kessab. The village is small but unusually rich in worship sites: three Armenian churches — an Apostolic (St. Mary), an Evangelical (Holy Trinity, opened 1970) and a Catholic (St. Michael, 1925) — served its 1,500-strong community. Nearby hill villages hold more shrines.

Just a mile away, the settlement of Karadouran contains Surp Stepanos, built in 909 AD, possibly the oldest standing Armenian church in Syria. Kessab’s Armenians long celebrated these churches, kept Armenian-language schools, and even ran an orphanage after the 1909 massacres. Farming fed every family: olives, figs, apples, and grapes from its orchards were the lifeblood of the town. In 2014, even as Syria’s war approached, Kessab remained mainly Armenian, its traditions intact. The village still hosted Armenian schools, community centers, and cultural associations — evidence of a deep, enduring heritage.

Under Siege

That sense of normalcy shattered in early 2014. On 21 March, Islamist rebel brigades launched a surprise assault on Kessab from the Turkish side of the border. Journalists reported a “multi-pronged attack” by Al-Nusra Front — which later rebranded as Hayat Tahrir al-Sham, now in power in Damascus — advancing directly from Turkey, allegedly even “supported by the Turkish military.” Within hours, lightly-armed border guards were overrun, the Turkish crossing was seized and Kessab’s Armenian quarter came under rebel control. Terrified residents fled along mountain tracks. “All but about 30 of the area’s roughly 2,500 residents fled within 48 hours of the attack,” reported The Washington Post. Many sought refuge in Latakia and Beirut. International outrage followed.

“The Armenian diaspora, including some celebrities, expressed outrage, demanding that the United States act to protect the Armenian community in Syria,” one account noted. In the end only one civilian from Kessab was reported killed by rebel fire, but churches were desecrated and crosses torn down in the attack. “Now it’s 2014, and we are being displaced again … But thank God that this time there is no massacre,” a 41-year-old farmer’s wife who arrived in Lebanon told the Washington Post. “We believe that, as Armenians, what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger.”

By mid-June 2014, forces of the regime of Bashar al-Assad had retaken Kessab. Refugees began trickling home almost at once — some 250 families returned within a day of liberation. What they found was heartbreaking. Kessab’s Armenian Catholic and Evangelical churches had been ruined and burnt by the rebels, along with the town’s cultural center. Mayor Vazgen Chaparian later summed it up: Kessab was “liberated” but “in a terrible plight,” he said. Homes and churches were still smoldering, and residents had “neither water nor electricity.”

Only the very old, men over 80, who had stayed behind emerged unharmed. Still, most of the community chose to rebuild. The Armenian General Benevolent Union and other diaspora charities mobilized in weeks after the attack, raising more than $1.7 million in aid for displaced Syrian Armenians. Church networks and friends in Lebanon and Armenia sent clothing and food. By late July the damage to Karadouran’s Surp Astvatsatsin Church had been repaired, its first liturgy since the events held on Vardavar (27 July), a traditional Armenian feast. Remarkably, even a few families from Armenia returned to help.

Heritage Sites and Restoration

The scars of war are still visible on Kessab’s sacred places — but so are the signs of renewal. As our SyriacPress reporter observed, Kessab is home to three Armenian churches and is surrounded by historic shrines.

In 2014, two of its churches were burned, but they have since been rebuilt. The Apostolic cathedral in Karadouran reopened in July 2014, and by 2017 the Evangelical Holy Trinity Church in town had been reconstructed. Today, all three churches in Kessab are again open for worship, and services are held regularly. Meanwhile, Kessab’s main Holy Mother of God Church is undergoing renovation which started in 2024 and continued through 2025. It was damaged by a 2023 earthquake and is now being rebuilt under the guidance of Bishop Magar of Holeb (Aleppo).

Even the rural shrines have seen care. The village of Karadouran still celebrates the old St. Stepanos Church (909 AD) as a heritage monument.

Kessab’s Armenian heritage sites — churches, school buildings, even cemeteries — are gradually being restored. This revival relies heavily on diaspora funding and church support. In December 2024 Archbishop Magar Ashkarian of Aleppo led a Christmas liturgy in Kessab and carried a blessing from Catholicos Aram I of the Armenian Church, who expresses his support to the Armenians of Kessab.

By 2025, Kessab was no longer in the headlines, but life remains hard. Many residents report basic needs are still not met. “There is no electricity,” one Armenian-Syrian said about the situation. “Our schools and churches are closed.” To her, it feels like a ghost town.

A village that once burst with church bells and market days now often sits dark. Security, too, is uncertain. Although Assad’s regime was ousted in late 2024, the new authorities — dominated by Sunni Islamists — have only tenuous control of the coastal region. In December 2024, Syrian troops reopened the Kessab border crossing with Turkey for the first time since 2011, but within weeks reports surfaced of pro-Turkey militias, mostly Turkmen Syrian groups, moving into the border hills near Kessab. “We are afraid,” one displaced man told SyriacPress reporter after clashes in the mountains, as news of sectarian killings filtered through. In daily life, villagers contend with other aftershocks of war. Nearly every Kessab family depends on farming, but in August 2025 catastrophic wildfires swept through the orchards just before harvest. One priest described the losses as “immense and painful.” Many families lost hundreds of fruit trees. Even worse, remnants of the war made firefighting difficult, the priest also noted that “landmines, planted over the years, limited firefighters” during the blaze. To help with these disasters, local elders formed a relief committee to document losses so that diaspora donors can replant trees and rebuild homes.

As one resident put it, Kessab today lives as an open question. Its people cherish a unique heritage but fear for its future. Until strong institutions return, life will likely remain a struggle. In March 2025, an old woman in Latakia city recalled her daughter’s voice trembling as she considered leaving.

Christians in the New Syria

Kessab’s fate is entwined with that of Syria’s dwindling Christian minority. Before 2011 perhaps 100,000 Armenians lived in Syria. Today only about 30,000 remain, many clustered in Holeb. On the eve of the war, Christians of all denominations numbered roughly 1.5 million, making up approximately 10% of Syria’s total population. By 2022 that share had fallen to around 2%, some 300,000 people.

Kessab — remote, resilient, and deeply Armenian — has come to symbolize both survival and loss. Its people are watched anxiously by Armenians around the world. Diaspora leaders and charities in Lebanon, Europe, the US, and Armenia have kept Kessab in their prayers and budgets. One Armenian-American columnist urged in late 2024 that, “our people in Syria need our support … There must never be a limitation on our compassion for fellow Armenians.” Whether that support will keep this village alive is a question hanging over Kessab’s ancient stones.

In Kessab today, a mixture of pride and sorrow endures. “Our roots are there,” one former resident said after the 2014 assault, “everything is there — but we can’t.” For now, the Armenian community remains, holding festivals in a war-scarred churchyard and teaching children the language of their grandparents. As one evacuee shrugged after reaching safety, “we believe that, as Armenians, what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger.” That resilience is a quiet vow that Kessab’s story, centuries old, is not yet finished.